Edwards Air Force Base

| Edwards Air Force Base

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Aerial photo of Edwards AFB | |||

| IATA: EDW – ICAO: KEDW – FAA LID: EDW | |||

| Summary | |||

| Airport type | Military: Air Force Base | ||

| Operator | United States Air Force | ||

| Location | Edwards, California | ||

| Built | 1933 | ||

| In use | 1948 - present (as AFB) | ||

| Commander | Major General David Eichhorn | ||

| Occupants | Air Force Flight Test Center | ||

| Elevation AMSL | 2,302 ft / 702 m | ||

| Website | |||

| Runways | |||

| Direction | Length | Surface | |

| ft | m | ||

| 04R/22L | 15,024 | 4,579 | Concrete |

| 04L/22R | 12,000 | 3,658 | Concrete |

| 06/24 | 8,000 | 2,438 | Concrete |

| Source: official site[1] and FAA[2] | |||

Edwards Air Force Base (IATA: EDW, ICAO: KEDW, FAA LID: EDW) is a United States Air Force base located on the border of Kern County, Los Angeles County, and San Bernardino County, California, in the Antelope Valley. It is 6 nautical miles (11 km; 6.9 mi) southwest of the central business district of North Edwards, California[2] and 7 miles (11 km) due east of Rosamond. It is named in memory of U.S. Air Force test pilot Glen Edwards, who died, along with the crew of five, June 5, 1948 northwest of the base while testing the YB-49 Flying Wing.

Contents |

Overview

Designated as the Air Force Flight Test Center (AFFTC), Edwards is home to the 412th Test Wing, the United States Air Force Test Pilot School, and NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center. It is currently operated and maintained by the 95th Air Base Wing as a part of the Air Force Materiel Command. Almost every United States military aircraft since the 1950s has been at least partially tested at Edwards, and it has been the site of many aviation breakthroughs as a result.

The base is strategically situated next to Rogers Dry Lake, an endorheic desert salt pan; its hard dry lake surface provides a natural extension to Edwards' runways. This large landing area, combined with excellent year-round weather, makes the base a perfect site for flight testing. The lake is a National Historic Landmark.[3]

Notable occurrences at Edwards include Chuck Yeager's famous flight where he broke the sound barrier in the Bell X-1, test flights of the North American X-15, the first landings of the Space Shuttle, and the 1986 around-the-world flight of the Rutan Voyager.

The base is also one of the largest purchasers of renewable energy in the nation, deriving 60 percent of its electricity from renewable sources, and is a lead partner in the United States Environmental Protection Agency's Green Power Partnership.

Originally known as the Muroc Army Air Field, the base was renamed on December 8, 1949 in memory of U.S. Air Force test pilot Glen Edwards (1918–48), who died 18 months earlier while testing the Northrop YB-49 flying wing.

Edwards has been an air base since 1933, when a cadre arrived from March Field in Riverside to lay out a bombing range for bomb crews and to set up tents. It has long been a home for flight research and testing and has subsequently been home to many of aviation's most important and daring research flights.

Previous names of Edwards AFB were:

- Muroc Lake Bombing and Gunnery Range, September 1933

- Army Air Base, Muroc Lake, July 23, 1942

- Army Air Base, Muroc, September 2, 1942

- Muroc Army Airfield, November 8, 1943

- Muroc Air Force Base, February 12, 1948.

Major commands

- Ninth Corps Area, USA, September 1933 - January 16, 1941

- Air Corps, September 1933 - March 1, 1935

- GHQAF, March 1, 1935 - January 16, 1941

- Southwest Air District, January 16, 1941 - March 11, 1941

- 4th AF, March 31, 1941 - July 17, 1944

- AAF Materiel and Services, July 17, 1944 - August 31, 1944

- AAF Technical Service Comd, August 31, 1944 - June 6, 1945

- Continental Air Forces, June 6, 1945 - October 16, 1945

- Air Technical Service Comd, October 16, 1945 - March 9, 1946

- Air Materiel Comd, March 9, 1946 - April 2, 1951

- Air Research and Development Comd, April 2, 1951 - April 1, 1961

- Air Force Systems Command, April 1, 1961 - July 1, 1992

- Air Force Materiel Command, July 1, 1992–present

Base operating units

- March Fld Range Maintenance Det, September 1933 - July 9, 1941

- Bombing and Gunnery Range Det, Muroc, July 9, 1941 - May 1, 1942

- 323d Base HQ and Air Base Sq, I May 1942 - April 1, 1944

- 421st AAF Base Unit, April 1, 1944 - October 16, 1945

- 4144th AAF Base Unit, October 16, 1945 - August 28, 1948

- HQ and HQ Sq 2759th AFB, August 28, 1948 - May 20, 1949

- 3076th Air Base Gp, May 20, 1949 - June 25, 1951

- 6510th Air Base Wg, June 25, 1951 - November 8, 1954

- 6510th Air Base Gp, November 8, 1954 - June 1, 1994

- 95th Air Base Wing, June 1, 1994–present

Early history

A water stop on the Southern Pacific Railroad since 1876, the site was largely unsettled until the early 20th century. In 1910, Ralph, Clifford and Effie Corum built a homestead on the edge of Rogers Lake. The Corums proved instrumental in attracting other settlers and building infrastructure in the area, and when a post office was commissioned for the area, they named it Muroc, a reversal of the Corum name, because there was already a town named Corum.

Under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Henry H. Arnold, the Army Air Corps selected a site next to the Rogers dry lake for a new bombing range in 1933. The airbase established to service the range was called Muroc Field. At this time, another colorful character in Edwards' history, Pancho Barnes, built her renowned Rancho Oro Verde Fly-Inn Dude Ranch that would be the scene of many parties and celebrations to come. The dry lake was a hive of hot rodding, with racing on the dry lakes. Incidentally, the runway that the Space Shuttle lands on follows the same route that racing took place on in the 1930s.

When Arnold became Chief of the Air Corps in 1938, the service was given a renewed focus on Research and Development. Muroc Field drew attention because the nearby dry lake was so flat that it could even serve as a giant runway ideal for flight testing. Accordingly, the base debuted its first major test aircraft when the P-59 Airacomet, America's first jet aircraft, lifted off on October 1, 1942. Over $120 million was spent developing the base in the 1940s, and it was expanded to 301,000 acres (470 sq mi; 1,220 km2). Included in this development was the base's main 15,000-foot (4,600 m) runway, which was completed in a single pour of concrete.

Post-war flight testing

After World War II, America found itself in an accelerating race for aerospace technology. Accordingly, the Air Force began the X-plane program in 1946, and development was largely centered at Muroc. The program grew to achieve stunning successes as the Bell X-1 became the first aircraft to break the sound barrier on October 14, 1947. Public attention was now firmly centered on Muroc Field, and test activity surged enormously.

So many aircraft were tested in the years after WWII that test pilots logged hundreds of hours each month, often in many different prototype planes. This inevitably led to accidents, and the death rate at Muroc surged. On January 27, 1950, the base was renamed after Glen Edwards, who died while testing a prototype Northrop YB-49. Test pilots were undeterred however, and Edwards AFB was designated the U.S. Air Force Flight Test Center on June 25, 1951. The X-plane program achieved further successes as the Bell X-2 achieved over 100,000 feet (30,000 m) of altitude and speeds greater than Mach 3 in 1956.

Throughout the 1950s, American airplanes broke absolute speed and altitude records on a regular basis at Edwards, but nothing compared with the arrival of the North American X-15 in 1961. Within a few short years, the X-15 topped Mach 4, 5, and 6, setting a speed record for piloted atmospheric flight of Mach 6.7 on October 3, 1967 that stands today. Furthermore, the X-15 became the first airplane to fly into space on July 19, 1963, when it achieved an altitude of 347,800 feet (106,000 m). Another aircraft gained world fame in the late 1960s at Edwards: The Lockheed YF-12A, a precursor to the SR-71 Blackbird, shattered nine records in one day of testing at Edwards. The SR-71's full capabilities are classified to this day, but the records set on May 1, 1965 included a sustained speed of 2,070 miles per hour (3,330 km/h) and an altitude of 80,257 feet (15 mi; 24 km).

On the ground

Extensive aviation research was also conducted on the ground at Edwards. Though they no longer exist, Edwards once hosted two rocket sled tracks that pioneered important developments and research for the Air Force. The first 2,000-foot (610 m) long track was constructed by Northrop in 1944 near what is currently the North Base. Originally intended for use as a development platform of a V-1 flying-bomb-style weapon, this project never left the drawing board. The track found use after the war as a test area for V-2 rockets captured from Nazi Germany in Operation Paperclip. Later, Dr. John Stapp appropriated the track and installed what was believed to be one of the most powerful mechanical braking systems ever constructed for use in his famous deceleration tests whereafter the press termed him "fastest man on earth" and the "Bravest man in the Air Force" for his world-changing MX981 project.

The results from the first track prompted the Air Force to investigate building a second, and in 1948 a new 10,000-foot (3,000 m) track was completed just south of Rogers Lake. This track was capable of supersonic speeds, and its first project was the development of the SM-62 Snark cruise missile. This track was so successful that an extension was constructed, and on May 13, 1959, the full 20,000-foot (6,100 m) track was opened. After the Navy had conducted research on the UGM-27 Polaris ballistic missile, the track was used for the development of ejection seats that could be used at supersonic speeds. Though this program was a success, a budgetary review concluded that the track was too expensive to maintain and the track was decommissioned on May 24, 1963. Before it was closed, a trial run set a world speed record of Mach 3.3 before the test car broke up. After its closure, the rails were pulled up to facilitate the straightening of Lancaster Boulevard.

Edwards AFB in the space age

After President Richard M. Nixon announced the Space Shuttle program on January 5, 1972, Edwards was chosen for Space Shuttle orbiter testing. The prototype Space Shuttle Enterprise was carried to altitude by the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) and released. In all, 13 test flights were conducted with the Enterprise and the SCA to determine their flight characteristics and handling. After Space Shuttle Columbia became the first Shuttle launched into orbit on April 12, 1981, it returned to Edwards for landing. The airbase's immense lakebeds and its proximity to Plant 42, where the Shuttle was serviced before relaunch, were important factors in its selection and it continued to serve as the primary landing area for the space shuttle until 1991. Since then, Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida has been favored. This saves the considerable cost of transporting the shuttle from California back to Florida, but Edwards AFB and the White Sands Space Harbor continue to serve as backups; Shuttles have landed at Edwards as recently as August 9, 2005 (STS-114), June 22, 2007 (STS-117), November 30, 2008 (STS-126), May 24, 2009 (STS-125), and September 11, 2009 (STS-128) due to rain and ceiling events at the KSC Shuttle Landing Facility. STS-126 was the only shuttle to land on temporary runway 04 at Edwards, as the refurbished main runway will be operational from STS-119 through to the scheduled retirement of the shuttles.[4]

The 1980s also saw Edwards host a demonstration of America's space warfare capabilities as a highly modified F-15 Eagle launched an ASM-135 anti-satellite missile at the dead P78-1 (or Solwind) satellite and destroyed it. In 1986, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager launched from Edwards to set a new aviation record by piloting the first non-stop, around-the-world flight on a single tank of fuel in the Rutan Voyager.

Books and movies

The base was the main location of the 1980 book written by Tom Wolfe, and subsequent movie adaption The Right Stuff. The book tells the story of some of the testing done at Edwards during the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, at the same time as the US Space Program was developing. Some of this history is revisited in the documentary The Legend of Pancho Barnes and the Happy Bottom Riding Club.

The base was the location of the flight line scene in the movie "Firefox" from 1982. The scene shows a General and a Colonel stepping out of a flight line truck, discussing if Clint Eastwood's character could handle the Firefox aircraft.

In the 2005 episode of the television series, NUMB3Rs, fighters from Edwards AFB were scrambled to intercept a UFO.

Present day Edwards

The most recent projects at Edwards are the F-35 Lightning II, F-22 Raptor, RQ-4 Global Hawk, YAL-1 Airborne Laser and B-52 synthetic fuel program. In addition, the C-17 Globemaster III flight test program is another major project at Edwards AFB. As well, the Department of Defense's massive development on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) has seen significant testing of prototypes at Edwards.

Unusually, Edwards has actually gained a few jobs in recent years under the DoD's Base Realignment and Closure process. As smaller bases have been decommissioned, their facilities and responsibilities have been consolidated at large bases like Edwards and China Lake. For example, Marine Aircraft Group 46, Detachment Bravo, two heavy lift helicopter squadrons, were assigned to Edwards following the closing of MCAS El Toro in May 1999.

Edwards is also home to several other Associate units from DOD, Air Force, Army, Navy, FAA, USPS and many companies that support the primary mission or the personnel stationed there.[5]

Since 2005, Space Shuttle landings have been common once again at Edwards.

Facilities

Main base

Edwards Main Base includes the Dryden Flight Research Center at its north end and is directly connected to the South Base. The Main Base airfield has a control tower, a TRACON (callsign Joshua), and a Radar Control Facility (callsign Sport). Its ICAO airport code is KEDW (IATA: EDW). As a military airbase, civilian access is severely restricted, but is possible with prior coordination and good reason. There are three lighted, paved runways:

- 04R/22L is 15,024 × 300 ft (4,579 × 91 m), and an extra 9,588 ft (2,922 m) of lakebed runway is available at its northerly end. It is equipped with arresting systems approximately 1,500 ft (460 m) from each end.

- 04L/22R is 12,000 × 200 ft (3,700 × 61 m) and was constructed to temporarily replace 04R/22L while it was being renovated in 2008.[6]

Both 4R and 4L have visual cues for the Space Shuttle to use on its approach.

- 06/24 is 8,000 × 50 ft (2,400 × 15 m) (this runway is technically part of the South Base) and an extra 10,158 × 210 ft (3,100 × 64 m) of lakebed runway is available at its easterly end.

There are 13 other official runways on the Rogers lakebed:

- 17/35 is 39,907 × 900 ft (12,000 × 270 m) (primary runway). It is actually marked as three adjacent 300 ft (91 m)-wide runways (L, C, and R). Imagery from the 1990s shows an additional approximately 7,500 ft (2,300 m) extending to the north from 17L/35R, including a visual cue and centerline markings that extend about 15,000 ft (4,600 m) down the currently declared portion of the runway. This extension and the centerline markings are faded in current imagery.

- 05L/23R is 22,175 × 300 ft (6,800 × 91 m)

- 05R/23L is 14,999 × 300 ft (4,600 × 91 m) and is immediately adjacent to 05L/23R at the 23L (easterly) end.

- 06/24 is 7,050 × 300 ft (2,100 × 91 m). This is not to be confused with the south base 06/24 paved runway (which also extends onto the lakebed), or the north base 06/24 paved runway.

- 07/25 is 23,100 × 300 ft (7,000 × 91 m)

- 09/27 is 9,991 × 300 ft (3,000 × 91 m)

- 12/30 is 9,235 × 600 ft (2,800 × 180 m). It is actually marked as two adjacent 300 ft (91 m)-wide runways (L and R). Runway 30 rolls out onto the compass rose, so its corresponding, unmarked, runway 12 is never used.

- 15/33 is 29,487 × 300 ft (9,000 × 91 m)

- 18/36 is 23,086 × 900 ft (7,000 × 270 m). It is actually marked as three adjacent 300 ft (91 m)-wide runways (L, C, and R).

The Rosamond lakebed has two runways painted on it:

- 02/20 is 4.0 miles (6.4 km) long

- 11/29 is 4.0 miles (6.4 km) long

The Main Base is home of the Benefield Anechoic Facility (BAF), an electromagnetic and radio frequency testing building. It is also home to the Air Force Flight Test Center Museum, which has over 15 aircraft on display.[7][8]

Dryden Flight Research Center

Contained inside Edwards Air Force Base is NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center (DFRC) where modern aircraft research is still active (e.g. the Boeing X-45). The DFRC is home to many of the world's most advanced aircraft. Notable recent research projects include the Controlled Impact Demonstration and the Linear Aerospike SR-71 Experiment. It is also the home of the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA), a modified Boeing 747 designed to carry the Space Shuttle back to Kennedy Space Center in the case the Orbiter lands at Edwards.

Air Force Rocket Research Laboratory

The Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), Propulsion Directorate maintains a rocket engine test facility on and around Leuhman Ridge, just east of Rogers Dry Lake. This facility traces its roots to early Army Air Corps activities.

In 1934, Colonel Hap Arnold assigned an Army Air Corps officer to survey a 300-square-mile (780 km2) area of the California desert in order to establish the Muroc remote bombing range. Luehman Ridge, the granite ridge, where two-thirds of the nation's high thrust static rocket stands are located, is named in honor of that young second lieutenant. Arno H. Luehman rose to the rank of Major General, USAF, before his retirement.

In the late 1940s, during the time of the United States Air Force formation, the facility was selected as a rocket test site. The first test stands were activated in 1952. The Rocket Engine Test Laboratory (RETL) and its personnel conducted "test and evaluation" of rocket sled engines as well as rocket engines for the Bell X1A, Boeing-Marquardt BOMARC, North American NAVAJO, MACE, Convair ATLAS, Douglas THOR, and other systems.

A major expansion of the facilities in 1957 created the basis for today's full spectrum research facility encompassing more than 65 square miles (170 km2) of the northeast corner of Edwards Air Force Base. It is currently (2008) valued at more than a billion dollars.

In 1959, elements of the Power Plant Laboratory at Dayton, Ohio, were relocated to the Edwards Rocket Engine Test facility. Also in 1959, the first tethered, vertical launch tests of the Minuteman I rocket were conducted in underground test silos. Shortly after these tests, the Minuteman I rocket completed its development and entered the U.S. Air Force's strategic arsenal.

During the 1960s, the need for continued operations and development of both future space and ballistic missile launch systems was signified by the re-designation of the site as the Air Force Rocket Propulsion Laboratory in 1953. Work began at this time on large segmented solid rocket motors, alternative liquid rocket engine boosters, high-speed turbo machinery, upper stage propulsion and satellite propulsion, all driven by the need to lessen the cost and complexity of the systems in use. The lab's personnel helped develop the powerful Saturn F-1 rockets which powered the Apollo manned moon missions. The F-1 was an outgrowth of the Air Force E-1 engine research program that transitioned into NASA's Saturn V rocket. In order to accommodate the testing of such large engines, a huge complex of multi-million pound static test stands was constructed on the northeast end of Luehman Ridge. The F-1's thrust chambers, nozzles, and entire engines were validated for NASA and tested with more than 5,000 firings on Luehman Ridge. Each rocket engine generated more than 1,500,000 pounds-force (6,700,000 N), consuming more than three tons of kerosene and liquid oxygen per second.

The late 1960s and 1970s saw the incremental integration of the Minuteman II into the United States Nuclear Arsenal. Also the inception and research and development of both the Peacekeeper and Small ICBM programs. This research continued throughout the 1980s while the Titan II ballistic missile was being phased out and utilized for early spacecraft launch. In this same period, research into the Air Force's XLR-129 liquid rocket engine had progressed. This engine's high speed turbopump mechanisms developed by the lab and its industrial partners provided the basis for the Space Shuttle's Main Engines. Large segmented solid rocket booster research and testing and the lab facilities insured that the industrial and technological basis for development of future large launch vehicles would be maintained.

In the mid-1980s, the facilities were reorganized and renamed the Air Force Astronautics Laboratory. Its personnel were busy with helping the nation recover from launch failures of the Titan 34-D and the Space Shuttle. Tests of O-rings at the lab independently verified the lack of resilience at very cold temperatures, helping to answer questions regarding the solid rocket boosters used on the Shuttle. At the same time, a large test stand capable of measuring more than eight million pounds of thrust was converted from a former Saturn F-1 large engine test stand to the first vertical large solid rocket booster test stand in the nation, capable of holding the booster in an upright position during the entire firing sequence and measuring its massive thrust. The tests were conducted successfully and assured the nation of access to space for Air Force launch vehicles.

The 1990s saw the consolidation of the myriad Air Force laboratories across the nation into four "SuperLabs." The Edwards rocket testing facilities, by then known as the Astronautics Lab, became an integral part of the Phillips "SuperLab," combining with the Geophysics Lab, Space Technology Center, and the Weapons Lab. The facility was renamed the Phillips Laboratory, Propulsion Directorate. Research at the Phillips Lab focused on the furthering of rocket propulsion technologies through several efforts. Efforts to develop Space Based Interceptors were considered in support of theater missile defense on the Theater High Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) program. The High Energy Density Matter (HEDM) project pushed the world of basic research in the area of physics and chemistry to find rocket propellants to surpass the capabilities of propellants existent at that time. The Titan IV Solid Rocket Booster static testing began and successfully ended its validation tests and acceptability as the newest booster in the Air Force, providing an additional 25 percent boost to the Titan launch system. Research and tests were conducted involving the nation's candidates for its next-generation launch systems, X-33, X-34, the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV), and a master plan for rocket propulsion technology covering 15 years called Integrated High Payoff Rocket Propulsion Technology (IHPRPT). The IHPRPT plan is a DoD/NASA/Industry initiative that lays out the goals and blueprints for achieving a doubling of rocket propulsion capability by 2010, covering space launch vehicles, tactical and ballistic missiles, and spacecraft propulsion.

A major milestone for the research lab and facility occurred on October 2, 1997. A ribbon-cutting ceremony marked the activation and completion of improvements to the lab’s historic Test Stand 1A. The stand is about to embark on its third era of testing the nation's rocket propulsion and launch capabilities. Initial use of the static test stand occurred in the 50's for full-up system testing of Convair's Atlas Intercontinental Ballistic Missile. The test stand was modified in the early 60's for use in developing and testing the Apollo era Rocketdyne F-1 rocket engine that propelled man to the moon. The third era supports the efforts of Boeing/Rocketdyne, a candidate for the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) launch program. Their Delta IV family of launch vehicles relies on a new core rocket engine technology called RS-68. The engine is designed to generate 650,000 pounds of thrust and is fueled by liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen.

The AFRL combined all four Superlabs and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) into a single lab commanded by Major General Paul, headquartered at Wright-Patterson AFB Ohio. The configuration of the nationwide lab is based on research and development topics. The Edwards facility is part of the new Propulsion Directorate which combines Wright-Patterson (Aeropropulsion) and Edwards (Rocket Propulsion) research efforts. No personnel moves were required. The Edwards rocket propulsion facility has approximately 500 researchers, engineers, technicians, and support staff split almost 50/50 between government/military employees and support contractors.

The rocket propulsion group leads a national plan called Integrated High Payoff Rocket Propulsion Technology (IHPRPT) to identify needs, timetables, and demonstrable goals for improvements to rocket propulsion technology. Participants in the plan include all military services, industry, and NASA. The rocket group's research and test projects are intregal with the plan and its goals. Their efforts covers ballistic launch, spacelift, tactical, and spacecraft propulsion research and development, with the end goal of doubling the nation's rocket propulsion capabilities by 2010. A key item in that plan is liquid fueled rocket propulsion component integration and testing, called Integrated Powerhead Demonstration or IPD. When complete, IPD technology will be available for application in future liquid rocket engines to enhance performance and save weight and costs. IPD is a combination of research efforts and validation testing to provide new, more efficient portions of the rocket engine that precondition and pump liquid fuels and oxidizers into the main engine. Dual-use components like Hydrostatic Bearings can be applied to rocket engines and commercial refrigeration units. Other efforts at the lab include electric and solar propulsion research, High Energy Density Matter (HEDM) propellant research, and Theater Missile Defense testing.

For more than half a century, the facility and its personnel, teamed together with government and industrial partners, have provided the United States with rocket propulsion that fits the needs of the nation and anticipates the future of propulsion technology. The Edwards Research Site, sometimes called 'The Rock', or simply 'The Lab' by those who work there, is part of the AFRL Propulsion Directorate, which is headquartered at the Wright Research Site, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio.

North Base

North Base is located at the north-west corner of Rogers Lake and is the site of the Air Force's most secret test programs at Edwards. The site has one 6,000 by 150 feet (1,800 × 46 m) paved runway, 06/24, and is accessed from the lakebed or via a single controlled road.

Geography

The largest feature of the 470 square miles (1,200 km2) that make up Edwards AFB are the Rogers Lake and Rosamond Lake dry lakes. These lake beds have served as emergency and scheduled landing sites for many aerospace projects including the Bell X-1, Lockheed U-2, SR-71 Blackbird, and the Space Shuttle. Even today, the lakebeds have black lines painted on it to mark seven official "runways" which are available for pilots operating in the area. Also painted on the dry lake beds near Dryden is the world's largest compass rose, which measures approximately 0.75 miles (1.21 km) in diameter. It is inclined to magnetic north (time & space/location dynamic, so when it was laid-out is relevant to where magnetic north has shifted from/to, but around 15.4 degrees east of true north) by Google Earth measurement (12.9 degrees stated by NASA runway map) and is used by pilots for calibrating heading indicators. The largest lake bed, Rogers, encompasses 44 square miles (110 km2) of desert. Because of Rogers' history in the space program, it was declared a National Historic Landmark.

The Rosamond dry lake bed encompasses 21 square miles (54 km2) and is also used for emergency landings and other flight research roles. Both lake beds are some of the lowest points in the Antelope Valley and they can collect large amounts of precipitation. Desert winds whip this seasonal water around on the lakebeds and the process polishes the lakebeds with a new, extremely flat surface; the Rosamond lake bed was measured to have an altitude deviation of 18 inches (460 mm) over a 30,000-foot (9,100 m) length; that's about 1 millimetre (0.039 in) altitude deviation over every 20 metres (66 ft) of length.

Environmental concerns

There are several protected and threatened species living in Edwards, the most notable being the desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii). It is unlawful to touch, harass or otherwise harm a desert tortoise. Edwards is careful not to interfere with this "gem in the desert". Another notable species is Yucca brevifolia: the taller members of this species are called Joshua trees.

Nearby bases

Another element of Edwards' success has been its proximity to other U.S. military bases. Edwards is close to the major city of Los Angeles, but it is also only a short flight south from Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake or Nellis Air Force Base that houses Area 51. Very secret aircraft developed at Edwards or other bases can easily and secretly be flown to a nearby base on a moonless night for maintenance or testing. Air Force Plant 42 and other defense research facilities in Palmdale are located only a few miles south of Edwards. The site of Lockheed Martin's famous Skunk Works, Plant 42 contains Boeing and Northrop Grumman aircraft manufacturing facilities as well. New, top-secret planes are often built at Plant 42 and then flown to the Main Base for night-time testing to maintain secrecy.

Edwards' proximity to other bases has led to the establishment of the jointly-administered R-2508 Special Use Airspace Complex. Containing Edwards, the Navy's China Lake and the Army's Fort Irwin bases, and a significant amount of land in between, R-2508 is completely restricted above FL200 for military use, and in some areas is restricted to the ground. The Department of Defense and its branches use this airspace to train pilots, and to test aircraft and weapons. Joint exercises are often conducted here, and sonic booms can be heard on a regular basis.

Demographics

The United States Census Bureau has designated Edwards Air Force Base as a separate census-designated place for statistical purposes.

As of the 2000 census[9], there were 5,909 people, 1,678 households, and 1,515 families residing in the base. The population density was 132.9 inhabitants per square kilometer (344 /sq mi). There were 1,783 housing units at an average density of 40.1 /km2 (104 /sq mi). The racial makeup of the base was 72.70% White, 10.42% Black or African American, 0.83% Native American, 4.35% Asian, 0.52% Pacific Islander, 5.43% from other races, and 5.74% from two or more races. 11.68% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 1,678 households out of which 67.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 84.9% were married couples living together, 3.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 9.7% were non-families. 9.1% of all households were made up of individuals and none had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.19 and the average family size was 3.38.

In the base the population was spread out with 36.1% under the age of 18, 19.9% from 18 to 24, 42.1% from 25 to 44, 1.8% from 45 to 64, and 0.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 23 years. For every 100 females there were 121.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 130.4 males.

The median income for a household in the base was $36,915, and the median income for a family was $36,767. Males had a median income of $27,118 versus $23,536 for females. The per capita income for the base was $13,190. About 1.0% of families and 1.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 1.3% of those under age 18 and none of those age 65 or over.

Politics

In the state legislature Edwards AFB is located in the 18th Senate District, represented by Republican Roy Ashburn, and in the 34th Assembly District, represented by Republican Bill Maze. Federally, Edwards AFB is located in California's 22nd congressional district, which has a Cook PVI of R +16[10] and is represented by Republican Kevin McCarthy.

See also

- Air Force Materiel Command

- John Stapp — Medical Doctor and research physicist; Contemporary and friend to Yeager and Murphy, known variously as Fastest human on earth, The bravest man in the Air Force, and The careful Daredevil, headed the historic MX981 rocket-sled research project.

- Aerospace Walk of Honor, in nearby Lancaster, California, honors notable Edwards test pilots.

- Murphy's Law — point of origination sometime in 1949. Popularized by John Stapp, one time neighbor of engineer Edward A. Murphy, his team coined the term which came out a few months afterwards in the first of Stapp's many press conferences over several decades. Murphy contributed measurement instruments that went awry to Doctor Stapp's MX981 project which sparked the laws naming to Murphy by Stapp's staff on his single visit to the program.

- Pancho Barnes — pioneer of women's aviation and the owner of the celebrated Happy Bottom Riding Club located on land annexed into Edwards

- North Edwards — home of retired chief master sergeants and NASA engineers as well as early clay mines vital to Muroc's fortunes.

- California World War II Army Airfields

- Mr. Monk and the Astronaut — an episode of the television series Monk filmed partially on location at Edwards Air Force Base.

References

- ↑ Edwards Air Force Base, official site

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 FAA Airport Master Record for EDW (Form 5010 PDF), effective 2008-04-10

- ↑ NHL Summary for Rogers Dry Lake

- ↑ Chris Bergin (November 30, 2008). "Endeavour lands at Edwards to conclude STS-126". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2008/11/endeavour-lands-at-edwards-to-conclude-sts-126/. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ [1] "Edwards Base Guide"

- ↑ "Edwards website - First flight marks temporary runway operational use". http://www.edwards.af.mil/news/story.asp?id=123099491. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ↑ Air Force Flight Test Center Museum

- ↑ Edwards AFB: USAF Flight Test Center Museum

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Will Gerrymandered Districts Stem the Wave of Voter Unrest?". Campaign Legal Center Blog. http://www.clcblog.org/blog_item-85.html. Retrieved 2007-10-20.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Air Force Historical Research Agency. This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Government document "Edwards Air Force Base".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Government document "Edwards Air Force Base".

External links

- Edwards Air Force Base, official site

- Edwards Air Force Base at GlobalSecurity.org

- Videos and Pictures of current and historical tests at DFRC

- AFRL PRS Homepage

- Documentary film about 'First Citizen of Edwards' Florence Pancho Barnes

- Aviation: From Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Historical record of balloons launched from the base between 1953 and 1954

- Edwards AFB Open House & Air Show, October 22, 2005

- Edwards AFB Open House Test Nation 2009

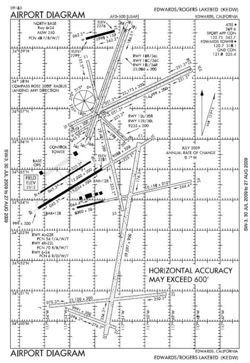

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective 23 Sep 2010

- Resources for this U.S. military airport:

- AirNav airport information for KEDW

- ASN accident history for EDW

- NOAA/NWS latest weather observations

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KEDW

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||